When it comes to addressing idling from air quality (environmental) and government control (legislative) standpoints, we think that lawmakers would be well served to look at the issue from two perspectives:

- “The Law of Unintended Consequences” perspective and

- an infrastructure perspective.

Before we explain, we must add the disclaimer that we are as desirous of having clean air to breathe as the next person.

Before we explain, we must add the disclaimer that we are as desirous of having clean air to breathe as the next person.

We also believe that other professional drivers want clean air to breathe.

We do not excuse those who deliberately pollute the air, but we do understand the bind that professional drivers are in (especially financially) to make their equipment compliant with clean air standards. Given that, let us press on…

The Law of Unintended Consequences

We address on our home sweet home page OTR drivers’ need to have the same types of creature comforts that others expect in their homes and businesses, including climate control and electrification (access to electricity). We further address the understudied problem of professional truck drivers having to stay in a hot truck.

Lawmakers who vote to restrict or eliminate idling across the board — including for drivers who have no idling alternatives — this is a “sentence” of discomfort and possibly health problems. Is it worth a driver’s life to preserve air quality, especially when first addressing infrastructure needs could help keep air cleaner? What about the lives of the motoring public that an affected driver is around?

The full impact of lawmakers’ decisions may not be realized until it is too late. But hopefully by addressing it on this page, we have done our part in the awakening that is sorely needed.

Infrastructure as it Affects Air Quality

In the sense that we are using the word on this page, infrastructure refers to roads (public, private and toll) that are used by drivers of large trucks to transport and deliver the commodities that are hauled. In the USA, roads are paid for from federal, state or county sources (sometimes as a result of fuel taxes or other taxes). As a population grows in various locations, more and more roads may need to be built to handle the traffic.

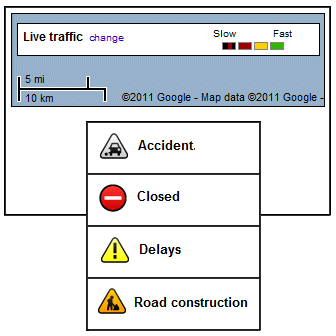

You may be aware that Google Maps has a “live traffic” indicator for major roads (mostly in the USA) that are marked according to the legend and icons as shown here:

If you look at a list of United States cities by population, you will find that the top two cities are

- New York, New York and

- Los Angeles, California.

Below are two images of the live traffic feature of Google Maps of these two cities and their surrounding areas around rush hour (in their respective time zones) on July 22, 2010.

Google Maps Live Traffic: New York, NY on July 22, 2010 at rush hour

Google Maps Live Traffic: Los Angeles, California on July 22, 2010 at rush hour

You can see a significant amount of yellow, red, and red-and-black lines (not to mention the icons), indicating that traffic is moving at slower than optimum speeds.

While idling does not take place except when a vehicle is stopped, slowdowns in traffic sometimes cause traffic jams (perhaps even stop-and-go traffic) that can last for miles. Don’t you think that this affects air quality? Of course!

Truck drivers often get stuck behind dense, slow moving or stopped traffic during periods of heavy congestion. Many times, these situations take place along in rush hour when commuters are commuting from the suburbs to the big cities. We have personally been stuck in very long traffic jams in the Washington, DC, area, particularly in the afternoons. If there was better infrastructure, slowdowns that require idling would not take place and air quality could be improved.

Commuting and Air Quality

So, how much extra fuel is burned, how much extra time is spent, and how much additional exhaust is expelled by drivers in the daily commute?

Congestion in Kentucky costs drivers billions annually

ttnews.com/articles/basetemplate.aspx?storyid=45016 (no longer online)

The “cost of traffic congestion increased in 2016 to an average of $1,400 for U.S. drivers” (link).

A May 17, 2017, article reported what the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI) revealed:

Traffic congestion on the US National Highway System (NHS) added more than $63.4 billion in operational costs to the trucking industry in 2015 … [that totaled] more than 996 million hours of lost productivity, which equates to 362,243 commercial truck drivers sitting idle for a working year.

According to the Texas A&M Transportation Institute’s August 26, 2015, press release:

According to the 2015 Urban Mobility Scorecard, travel delays due to traffic congestion caused drivers to waste more than 3 billion gallons of fuel and kept travelers stuck in their cars for nearly 7 billion extra hours – 42 hours per rush-hour commuter. The total nationwide price tag: $160 billion, or $960 per commuter.

Here’s an interesting article: “What’s Your Commute Time Worth?”

nytimes.com/2016/10/30/realestate/whats-your-commute-time-worth/ (no longer online)

Air Quality and Environmental Concern

According to the FMCSA in their publication “2016 Pocket Guide to Large Truck and Bus Statistics”(1):

In 2014, among the 260,350,938 total registered vehicles in the United States, 8,328,759 were single-unit trucks (straight trucks), 2,577,197 were combination trucks (tractor-trailers),and 872,027 were buses. Also in 2014, there were 3,025.7 billion vehicle miles traveled (VMT) by all motor vehicles. Large trucks traveled 279.1 billion of those miles (9.2 percent of the total), and buses traveled 16.0 billion of those miles (0.5 percent of the total).”

So if elected officials are concerned about exhaust emissions from vehicles, it is reasonable to target the majority of vehicles that produce it?

One could argue that the exhaust from gasoline engines is not the same as exhaust from diesel engines, but there are plenty of smaller vehicles with diesel engines on the road, are there not?

Sometimes, people think that all large trucks are major contributors to major amounts of air pollution.

Take for example these photographs here, here and here that show huge amounts of soot and visible exhaust being thrown in the air through the stacks of large trucks.

We have personally rarely seen this kind of exhaust from large trucks.

It should be noted that four-wheeled vehicles can also generate massive amounts of visible exhaust, such as shown in photographs here.

Some states are so concerned about this issue that they have developed a division of air quality, such as North Carolina, the state in which a trucking company for which Mike used to work is headquartered. This agency addresses the issues:

Reducing Idle Time through Idle Limiters

Some trucks have been designed to automatically shut off after a few minutes, to keep them from idling too long.

However, as was the case with the last Freightliner Cascadia Mike drove, the idle limiter could be overridden.

Reducing Emissions through Certified Clean Idle

Some trucks have diesel particular filters or “certified clean idle” technology that is supposed to eliminate the fine diesel particulate that can be emitted during idling. These vehicles all display a “Certified Clean Idle” decal like the one shown here.

Some trucks have diesel particular filters or “certified clean idle” technology that is supposed to eliminate the fine diesel particulate that can be emitted during idling. These vehicles all display a “Certified Clean Idle” decal like the one shown here.

Some of the anti-idle jurisdictions provide an exception to allow vehicles that display the decal to idle.

Likewise, some anti-idle zones provide for idling when the temperatures fall below a certain temperature or rise above it.

While local government bodies have every right to control the quality of air in their jurisdictions, elected officials must understand that the restrictions can have significant consequences on the lives of truckers and those with whom they share the road.

![]() Money saving tip: While it is unreasonable to expect that professional truck drivers will be able to completely eliminate idling while driving, they can aim (if their Hours of Service permit it) to enter and exit heavily populated areas during non-rush hour periods. (Running straight through an area reduces the exhaust released there, which in turn means air quality there is not harmed.)

Money saving tip: While it is unreasonable to expect that professional truck drivers will be able to completely eliminate idling while driving, they can aim (if their Hours of Service permit it) to enter and exit heavily populated areas during non-rush hour periods. (Running straight through an area reduces the exhaust released there, which in turn means air quality there is not harmed.)

For example, once Mike needed to make a trip from Milford, Connecticut to Greensboro, North Carolina during one driving period. By the shortest practical route, the trip is about 605 miles. In order to make sure that he made good time, he had to time leaving Milford such that he could avoid rush hour in and around New York City, Washington, DC and Richmond, VA. By leaving very early in the morning, he was able to do so.

Even though a truck may be equipped with “certified clean idle” technology, it is still costly to idle a truck when parked.

Seek alternatives that can provide climate control and electrification without idling your truck.

Return from Air Quality, Idling, the Environment and Trucker Comfort to our Truck Operations page or our Truck Drivers Money Saving Tips home page.

References:

1. ntl.bts.gov/lib/59000/59100/59189/2016_Pocket_Guide_to_Large_Truck_and_Bus_Statistics.pdf (no longer online)